What's in a name?

Often when we talk about accessibility problems, we end up talking about a number of different errors that all boil down to a missing accessible name: form fields without labels, images without alts, icon buttons without readable text, and many more. A missing or incorrect accessible name in some form or other is right up there with poor color contrast in the list of most common accessibility errors across the web.

More recently, a greater awareness of accessibility and an increase in the use of ARIA attributes has resulted in a sort of reverse naming problem, where elements that cannot or should not be named get artificial names through ARIA. You see this in <div>'s and <span>'s with aria-label's, or links and buttons whose programmatic name has been manually defined to be different than their visible text.

While an improperly added name is a step up from a missing one, it will often give the illusion of accessibility while masking an underlying problem that remains unaddressed. Both forgetting a name entirely and adding too many names result from not understanding when and how to properly give an element a name.

What is a "name"?

There are many different terms that are used to talk about a missing or incorrect accessible name, depending on context. For images, it can be "alternative text" or "the alt attribute"; for tables, "caption"; and for form fields, we usually talk about labels. Here's a non-comprehensive list of terms and concepts that all boil down to talking about names:

- labels, the

<label>element, and associating labels with form fields - table captions

- image alt text

- the

<legend>element - an SVG

<title>element aria-labelandaria-labelledby

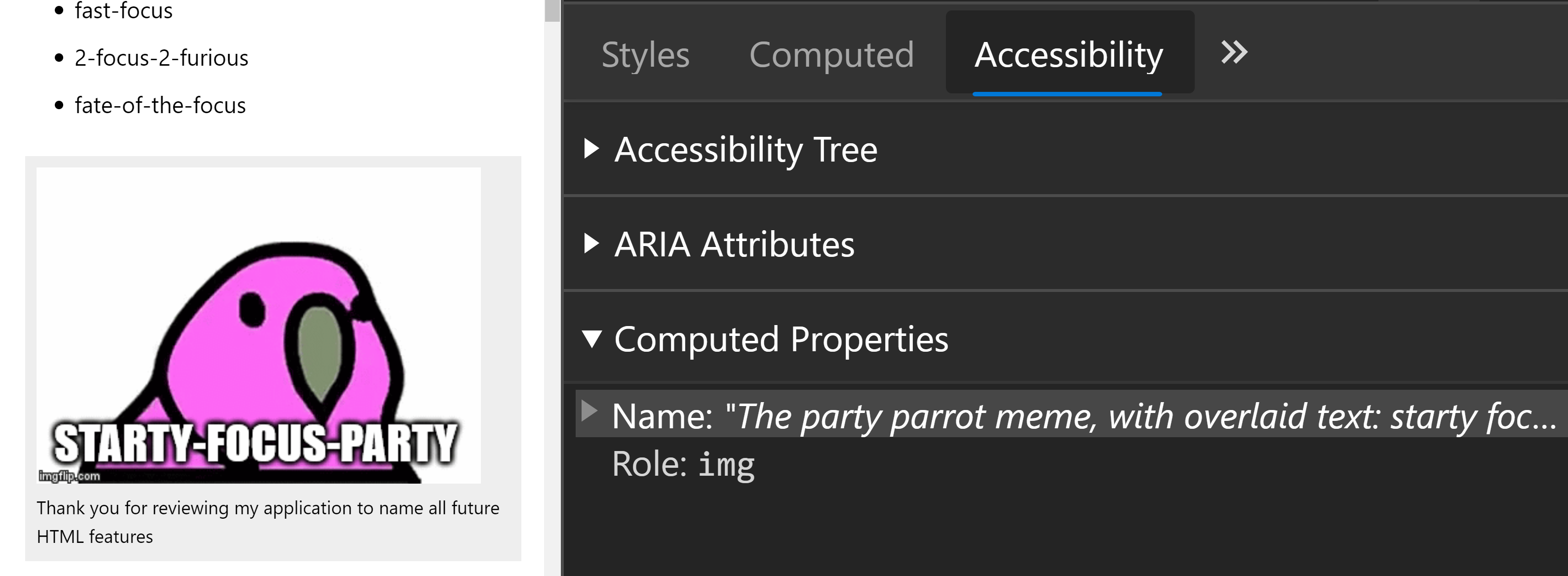

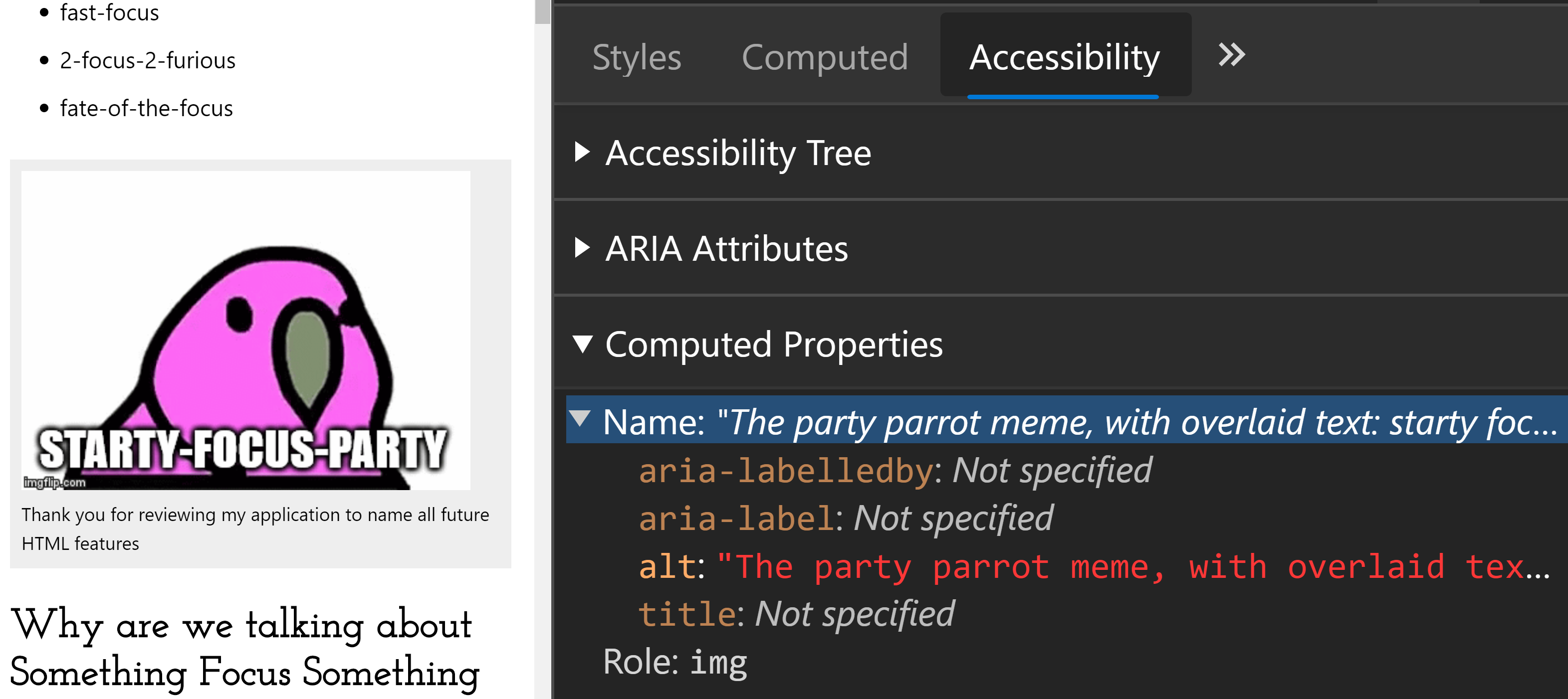

The reason I'm using "name" or "accessible name" to refer to all of these different concepts is because although they differ in HTML, they all end up mapping to the "name" property (or equivalent) in accessibility APIs and the browser's internal accessibility tree. For example, this screenshot shows how an <img> element's alt attribute is represented in Microsoft Edge's accessibility dev tools:

Most browsers will also let you view exactly where that computed name came from; in this case, the alt attribute:

If you wished to open up Accessibility Insights for Windows, you could see the same string defined in the image node's Name property in the underlying accessibility API.

What needs a name?

Not every element can support an accessible name, and even among those that can, not every one should. For example, a <section> element can be named with aria-label or aria-labelledby, but doing so will promote it to being a landmark, which isn't always desired. A list can also be named, though doing so is uncommon and not needed unless there's some context-specific reason for doing so. So, if some elements always need names, others may or may not benefit from a name, and others cannot be named at all, how do you know which is which?

There are a few general categories of elements that should always be named:

-

Interactive elements:

These include all form controls, links, buttons, and also complex interactive widgets like tabs, menus, listboxes, and so on. -

Other focusable elements:

Although generally non-interactive elements should not be focusable, there are some exceptions like client-side routing with focus management, a modal dialog, or the target of a skip link. Anything that can receive keyboard focus, whether through tabbing or scripting, should have an accessible name. -

Charts and graphics:

Meaningful images, graphs, canvas visuals, and other graphical content needs to be labelled with alternative text. Images and graphics that are not meaningful should be removed from the accessibility tree: with an<img>tag, this is done with an emptyalt="", andaria-hidden="true"works for other elements. -

Landmarks and labelled form groups:

Sets of checkboxes and radio buttons are nearly always within a form group, or a form group could contain multiple related text inputs, e.g. for a credit card. They should always have an accessible name that matches the visible group label. Traditionally this is done with the<fieldset>and<legend>elements, but can also be accomplished withrole="group"andaria-label/aria-labelledby.Landmarks need an accessible name when there are multiple instances of the same type of landmark on a page, such as a main navigation region together with a supplementary navigation region. Generic landmarks (with

role="region") always need an accessible name.

There are multiple different WCAG criteria that cover failing to give an accessible name to an element that needs one. There's Name, Role, Value for interactive controls lacking a name; Non-text content for naming, well, non-text content; Link Purpose (in context) for links with missing or poorly written names; then there's the catch-all Info and Relationships for any other scenario where meaning is implied by visual cues or context but not present programmatically.

How do you name an element?

Contrary to what you may think, naming an element involves neither a birth certificate nor the HTML name attribute. The name attribute is never directly exposed to the user, and is used only when submitting forms. Birth certificates have thus far been ignored by spec authors as a potential method for naming controls, but perhaps when web UI becomes sentient and self-propagating, we'll need to revisit that.

Right now, there are four different types of ways an element can be assigned a name: from author, from content, from encapsulation, and from legend. The last two are highly specific to certain form elements:

Name from encapsulation, using the <label> element:

<label>

<input type="checkbox">

This text will be the checkbox input's name

</label>Name from legend, which sounds epic but ultimately only refers to the <legend> element:

<fieldset>

<legend>This text will name the fieldset element, as long as the legend is the first child</legend>

<!-- some form elements go here -->

</fieldset>Most of the time when naming elements, you'll be using either a name from author, or name from content. Both of these techniques are likely familiar, even if the particular phrases "name from author" and "name from content" sound more like dry spec terms than actual words real people would say to each other.

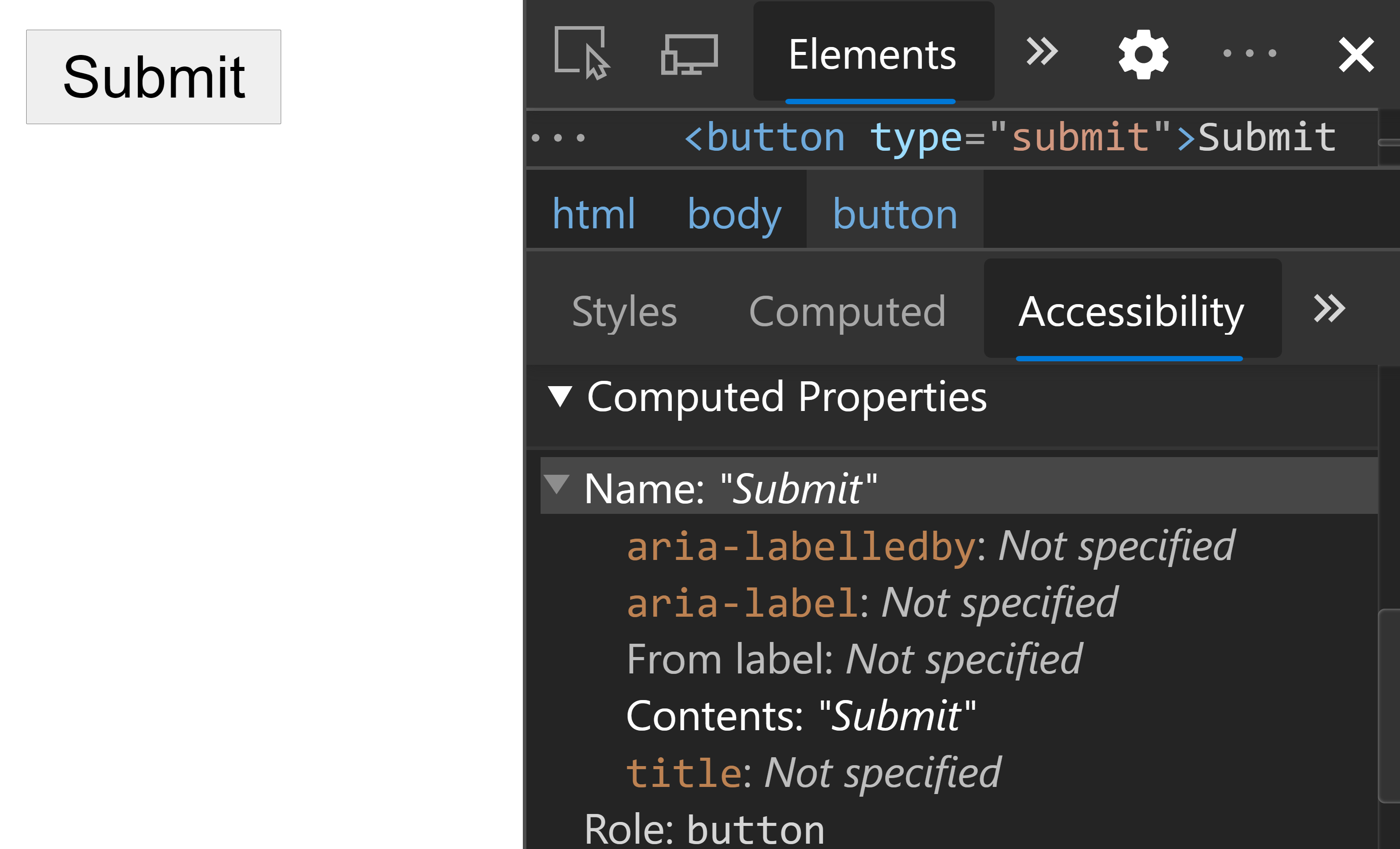

"Name from content" in its simplest form means an element's accessible name comes from its text content. Take the following example of a submit button that reads "Submit" (because I am a creative person):

<button type="submit">Submit</button>If you were to view that in a browser, you would see that the calculated name of the button is "Submit", and that the source is the button's contents:

A button with text content is a simple example; it's also possible to have non-text content contribute to an element's accessible name. In the following example, a link contains both text and an image with alt text. In it, the image gets its name from the alt attribute, and the link is named by the combination of all plain text and other named elements within it:

<a href="#">

<img src="images/twitter-icon.png" alt="Twitter.">

<span>Your daily source of all current-events-related anxiety.</span>

</a>

The image's alt attribute is actually an example of a name from author, nested inside the link's name from content. "Name from author" refers to assigning a name to an element directly, either by passing a string to an attribute like alt or aria-label, or through the use of an associated labeling element, like <label for="input-id">.

Some examples of defining a name from author include:

aria-labelaria-labelledby- the

<label>element, associated with an<input>byid - the

altattribute on an<img> - the

<caption>element in a<table>

Some elements with roles such as table and list, or landmark roles like navigation and main, only support name from author. If these elements are given a name through aria-label or aria-labelledby, screen readers will generally read that name when the user first enters the element, and then go on to read the element's content. This is because the content exists separately from the accessible name, so both the content and the name (if provided) are read separately.

In contrast, roles that support both name from author and name from content will only ever read one or the other. If a name from author is provided, the element's content will be entirely ignored. So if we were to consider the following extremely realistic example snippet:

<button aria-label="Cats are the best">Dogs are the best</button>The resulting button would have an accessible name of "Cats are the best", and someone using a screen reader would not encounter the string "Dogs are the best". A name from author will always override name from content, when both are supported.

There is an entire spec governing the full set of steps that browsers must take to determine the accessible name and description for any nameable or describable element. It is arcane and complex, and can generally be ignored by web developers. Here is a reduced summary of accessible name methods, ordered from what will override everything else (1) to what will only be used if no other methods are present (4):

aria-labelledbyaria-label- Native HTML methods: alt, the

<label>element, text content - Fallback attributes:

titleandplaceholder

Ideally, a single control will only be named using one method, so the exact way browsers calculate an accessible name should not matter much (unless you work on browser accessibility, in which case, thank you). Generally when in doubt, consult the accessibility information in your browser's developer tools. That will tell you both the calculated accessible name, and where it's coming from.

While there are a good number of possible ways to name a control, not all options are created equal. Rather than go into the nuances of why to choose a <label> element over aria-label here, I'd rather link to the article Adrian Roselli has already written on his priority of methods for labeling a control. The TL;DR is:

- Native HTML techniques (the

<label>element, text content,alt, etc.) aria-labelledby- visually hidden text content

aria-label

His article goes into more of the reasons around why some methods are better than others, which I won't duplicate.

One last note on adding an accessible name: the name must be added directly to the element that you intend to be named. If you want to name a table using the aria-labelledby attribute, then that attribute must be on the <table> or role="table" element. Putting aria-labelledby on a parent of the table will do nothing at all.

Which elements and roles can be named?

Every ARIA role falls into one of three naming possibilities: either it must have a name, it can optionally be named, or it cannot be named at all. Throw in the different possibilities for naming (from author, from content, from encapsulation, and from legend), and it gets to be a bit too much to keep track of.

Luckily, the ARIA spec has a section listing every single role that can be named, broken down by the naming method. Roles that require names are designated with "(name required)". Here are the sections where you can find the naming information:

The ARIA spec lists these only by role and not by element, but if you're not sure which role an element has by default, you can look it up in the HTML AAM spec. If an explicit role attribute is present, it will override the default role mapping in HTML AAM. For example:

<button>: look up thebuttonrole<button role="tab">: look up thetabrole

While the most common problem is for one of the "name required" roles to lack an accessible name, sometimes the reverse occurs and an element that cannot be named -- e.g. a <div> or <span> -- is given an aria-label or aria-labelledby. A couple cases where I've seen this happen include a <span aria-label="some text"> wrapping a font icon, or an aria-label added to a div in a card pattern.

Both of these examples come from good intentions, and an active attempt to create better accessibility. On the plus side, a few extra aria-label's on unnameable elements like this won't cause any negative side effects. The main danger is that the illusion of having given something an accessible name will obscure underlying issues. Usually the fix is to revisit which elements and roles should be used, or to reconsider what really needs a name.

In the case of the font icon example, the best solution would likely change the element into an image with role="img", which can then be given a name:

<span aria-label="name of icon" role="img"></span>A generic wrapping <div> for something like a card pattern is more complex. Does that section of content really need its own name, separate from the content within it? If this grouping of content is important enough to be named, then it should probably be exposed as some sort of group. Would an existing HTML pattern like a list fit your use case? Is there another element or role that would fit better?

A card pattern could be exposed as a list item within a list (as Heydon does in his card pattern), or perhaps as an article role. Both those roles (listitem and article) can be given a name from author, but that doesn't mean they need one. To decide whether a name-optional element would benefit from a name in this case as in others, the best thing to do is to consider how a programmatic name will translate into actual user experience. And then, of course, check those assumptions with people who rely on assistive technologies.

How is the accessible name used by assistive tech?

The programmatically exposed accessible name is primarily used by screen readers (including screen readers with braille displays) and voice control software. Voice control software can vary a lot in whether it uses the accessible name, text content, or some combination of the two. The programmatic name is not presented directly to the user, but consumed under the hood when a user issues a command like "press submit button."

Screen readers do present the accessible name directly to the user, in a number of different ways depending on the mode of interaction and the type of element that is named:

Direct interaction

The most straightforward way a screen reader exposes the accessible name is when the user interacts directly with the named element. This can come in the form of tabbing to a focusable element like a form field, link, or button, which is often the most beginner-friendly way of using a screen reader.

Another way to directly interact with an element is to use the screen reader's virtual cursor to move through a page, using sets of commands specific to each screen reader. This will present either the accessible name of a nameable control (heading, link, button, etc.), or a text string in the case of unnameable elements (divs, paragraphs, and so on).

Container roles

There is another type of nameable element that I'm going to call container roles, which include landmark regions, forms, lists, dialogs, tables, tabpanels, and generic groups. Usually when a screen reader user navigates the page, they will enter and exit these elements without interacting with them directly (emphasis on "usually"). If named, the name will generally be read when the screen reader's cursor first enters the container role, depending on the screen reader's support for that role (test everything).

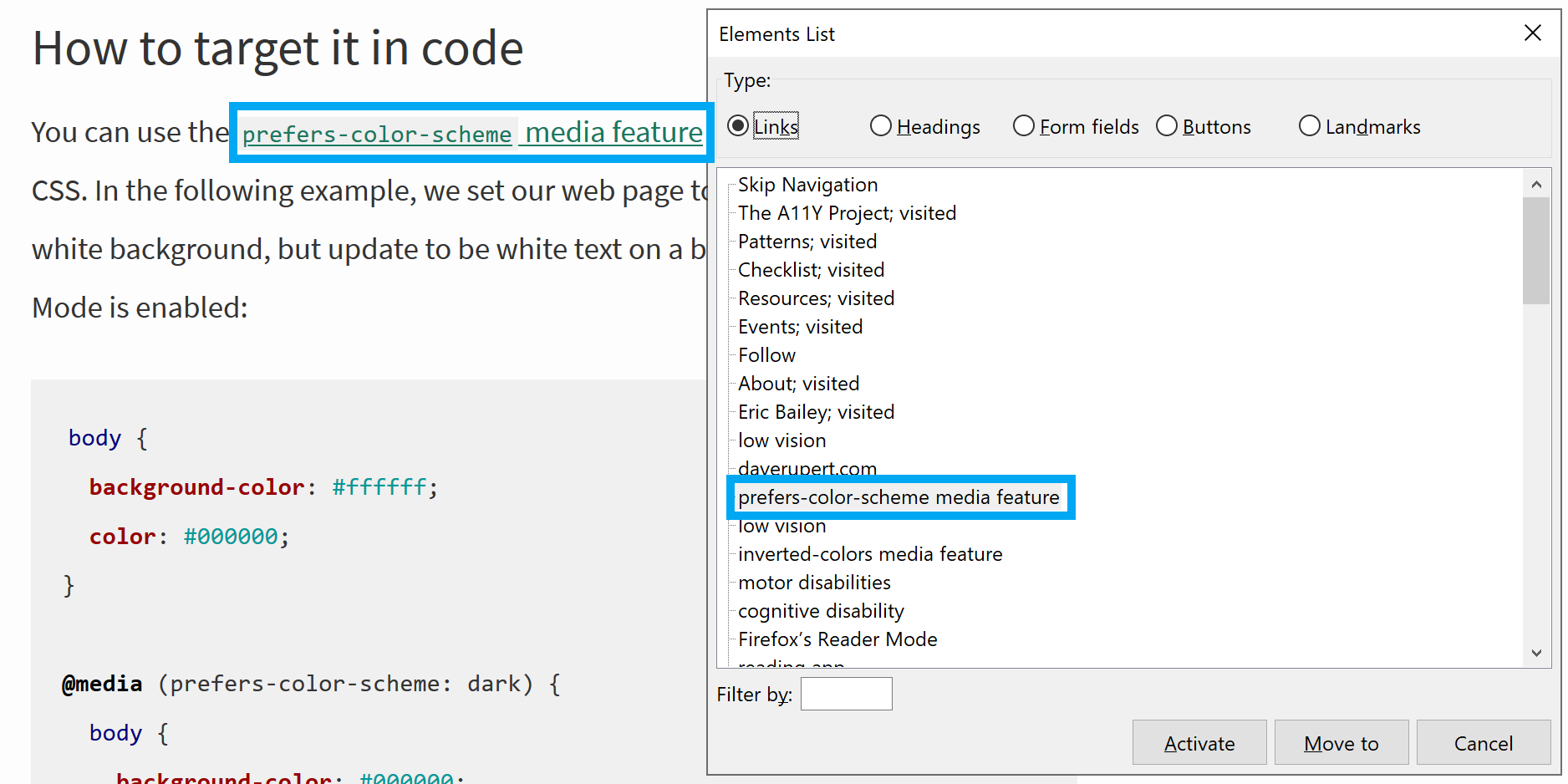

Elements list

One last way of consuming an accessible name is in an elements list. With an elements list, a screen reader user can review all elements of a particular type (e.g. links) out of context. Here's an example of what that looks like in NVDA:

The elements list is one example of when it is important to write unique, descriptive accessible names. Multiple duplicate buttons under different headings, or link names that only make sense in context will be confusing and unhelpful in the elements list.

How do you write a good name?

A developer's blog (or at least this developer's blog) is probably not the best place to look for advice on the writing process. I personally have enough trouble trying to name variables in code that no one else will ever read. Instead, try this page of writing tips from the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI), or this video on writing good labels from Jordyn Castor at Apple.

Instead, let's go over some general accessibility tips for writing a good name:

- Avoid including the type of control in the name

The type of control will already be communicated by screen readers. For example, naming a submit button "Submit button" will result in a redundant announcement, e.g. "Submit button button". - Make names unique

Unique names help screen reader users scanning controls directly without needing to examine surrounding context, and they also help sighted users by reducing the cognitive load required to determine the purpose of a control. Visually scanning an online store's buttons is easier when each has a unique name like "shop computers" and "shop laptops", and harder when all of them read "shop now". The exception is when multiple controls do the exact same thing. For example, there are two links named "card pattern" on this page, but they both go to the same URL. - Make names easy to skim

Concise, descriptive names are easier to quickly skim, and reduce the time required to process and comprehend each individual control. This is particularly important when many similar named items appear grouped together, such as row headers in a table, or options in a listbox. If all the names share a common string, putting the most unique, relevant information first will make them faster to skim. So a list of dates would do better as "13 April 2020" rather than "April 13, 2020".

When should you override the visual name?

Sometimes the desire to provide a unique, descriptive name to screen readers can conflict with an existing design, or lead to arguments with others whose opinions are not entirely based in a desire for accessibility. In those cases, it can be tempting to accept less-than-ideal visual labels while modifying the accessible name behind the scenes. For example, a developer tasked with improving the accessibility of an online storefront with 10 "Shop now" links might end up adding a more descriptive aria-label to each link while keeping the visual text the same:

<!-- Don't do this -->

<a href="/shop/dresses" aria-label="Shop Dresses">Shop Now</a>This is not ideal for a number of reasons, even though on first consideration it seems to improve the screen reader experience without the uncomfortable messiness of revisiting design. Unfortunately, creating separate visual and programmatic names causes its own new set of problems.

To start with, not all screen reader users are blind. People with low vision who use some form of magnification or high contrast might use a screen reader as a supplement. Others with no visual impairments might prefer to listen to information rather than look at it for cognitive or sensory reasons. It is not all that unusual for someone to listen to the programmatic name with a screen reader while also looking at the visual label. If those two diverge, it could be jarring and cause confusion. Even fully blind screen reader users sometimes need to communicate with tech support or sighted colleagues, and separate content can make that difficult.

Different names can also cause problems for someone using a voice control software like Dragon Naturally Speaking. A Dragon user confronted with 10 "shop now" links would not be able to take advantage of the unique but invisible "shop dresses" programmatic name. In WCAG 2.1 there is a new criterion, Label in Name, specifically for improving this experience.

All this doesn't mean that there are never good reasons to create separate programmatic and visual names. In cases where the visual name is an icon or graphic, or the visual context is conveying information that cannot be easily captured as a text label, a custom programmatic name might make sense.

A good time to use hidden text or an aria-label is when you have no visible text labeling an element, but where a sighted user gets that information through visual context. One concrete example is for landmark regions of the page: you might have a main navigation menu at the top of the page, and a secondary sidebar navigation for something like content categories. The position and visual style of each navigation region tells the user its importance, and adding short accessible names like "main" and "categories" communicates that same information programmatically. Some other examples of good use cases for hidden text, an aria-label, or other non-visual label include:

- Alt text for images

- Naming an icon button

- Naming a container widget like a dialog, feed, tabpanel, or list. If a heading or other text exists that visually labels the container,

aria-labelledbyis a better choice thanaria-label

Practical accessibility doesn't always match ideal accessibility, and there will almost certainly be times when a design or content change just isn't happening, for whatever reason. In those cases, improving the accessible name is better than nothing. Just take care to include the visual label within the accessible name (ideally at the start), and try to write something that will not cause confusion when used together with the visual text.

Tooltips, placeholders, names, and duplicate announcements

A while back, I wrote a rant small article about some of the accessibility challenges of tooltips. One section dealt with whether the tooltip should form the name or the description of the control it is attached to. Essentially, sometimes a tooltip will function visually as the accessible name (common with icon buttons) and sometimes it will provide additional descriptive text. The danger here is that using a title attribute to provide both a tooltip and an accessible description that is the same as the control's accessible name can create duplicate announcements. Sometimes. It depends.

The same inconsistent double announcements exist with a name and placeholder, although the specifics of which screen readers and browsers double up may differ. (Full disclosure: I only tested in a few screen readers to verify inconsistency, and testing results go out of date quickly in any case).

Both the title and placeholder attributes will be used as fallback sources for the accessible name, so using them that way can be a tempting way to resolve the duplicate announcement problem. However, relying on either title or placeholder as the label for a control causes many, many accessibility problems that go beyond simple programmatic support.

Seriously, don't do it:

- The Trials and Tribulations of the Title Attribute by Scott O'Hara

- Don't Rely on the Title Attribute for Accessibility by the mediacurrent team

- Using the HTML title attribute – updated March 2020 by Steve Faulkner

- Don’t Use The Placeholder Attribute by Eric Bailey

- How-to: Use placeholder attributes from the A11y Project

- placeholder - the piss-take label by Steve Faulkner

- Placeholder research from the Web Accessibility Initiative's low vision accessibility task force

- Placeholders in Form Fields Are Harmful by Kate Sherwin

Further reading

Thanks for reading this all the way to the end! I highly recommend also reading Adrian's naming article, and the AccName specification for particularly intrepid and detail-oriented developers.

- Priority of methods for labeling a control from Adrian Roselli

- Accessible name and description computation

- What's in a Name, an article by the same name from Glen Walker